Back علاج بالليثيوم Arabic لیتیم (پزشکی) AZB Cyfansoddion Lithiwm Welsh Lithiumtherapie German Litio (medicamento) Spanish لیتیم (دارو) Persian Litium (lääke) Finnish Sel de lithium French ליתיום (תרופה) HE Lítiumterápia Hungarian

| |

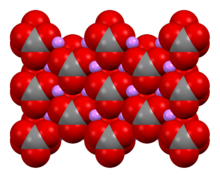

Lithium carbonate, an example of a lithium salt | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Many[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681039 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, parenteral |

| Drug class | Mood stabilizer |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Depends on formulation |

| Protein binding | None |

| Metabolism | Kidney |

| Elimination half-life | 24 h, 36 h (elderly)[4] |

| Excretion | >95% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | Li+ |

| Molar mass | 6.94 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Certain lithium compounds, also known as lithium salts, are used as psychiatric medication,[4] primarily for bipolar disorder and for major depressive disorder.[4] Lithium is taken orally (by mouth).[4]

Common side effects include increased urination, shakiness of the hands, and increased thirst.[4] Serious side effects include hypothyroidism, diabetes insipidus, and lithium toxicity.[4] Blood level monitoring is recommended to decrease the risk of potential toxicity.[4] If levels become too high, diarrhea, vomiting, poor coordination, sleepiness, and ringing in the ears may occur.[4] Lithium is teratogenic at high doses, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy. The use of lithium while breastfeeding is controversial; however, many international health authorities advise against it, and the long-term outcomes of perinatal lithium exposure have not been studied.[5] The American Academy of Pediatrics lists lithium as contraindicated for pregnancy and lactation.[6] The United States Food and Drug Administration categorizes lithium as having positive evidence of risk for pregnancy and possible hazardous risk for lactation.[6][7]

Lithium salts are classified as mood stabilizers.[4] Lithium's mechanism of action is not known.[4]

In the nineteenth century, lithium was used in people who had gout, epilepsy, and cancer.[8] Its use in the treatment of mental disorders began with Carl Lange in Denmark[9] and William Alexander Hammond in New York City,[10] who used lithium to treat mania from the 1870s onwards, based on now-discredited theories involving its effect on uric acid. Use of lithium for mental disorders was re-established (on a different theoretical basis) in 1948 by John Cade in Australia.[8] Lithium carbonate is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines,[11] and is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2020, it was the 197th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[12][13] It appears to be under-utilised in older people,[14] though the reason for that is unclear.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

brandswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Lithium Salts". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Poels EM, Bijma HH, Galbally M, Bergink V (December 2018). "Lithium during pregnancy and after delivery: a review". International Journal of Bipolar Disorders. 6 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0135-7. PMC 6274637. PMID 30506447.

- ^ a b Armstrong C (15 September 2008). "ACOG Guidelines on Psychiatric Medication Use During Pregnancy and Lactation". American Family Physician. 78 (6): 772. ISSN 0002-838X. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Lithium Carbonate Medication Guide" (PDF). U.S. FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b Sneader W (2005). Drug discovery : a history (Rev. and updated ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Lenox RH, Watson DG (February 1994). "Lithium and the brain: a psychopharmacological strategy to a molecular basis for manic depressive illness". Clinical Chemistry. 40 (2): 309–314. doi:10.1093/clinchem/40.2.309. PMID 8313612.

- ^ Mitchell PB, Hadzi-Pavlovic D (2000). "Lithium treatment for bipolar disorder" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (4): 515–517. PMC 2560742. PMID 10885179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2012.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Lithium – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Almeida OP, Etherton-Beer C, Kelty E, Sanfilippo F, Preen DB, Page A (27 March 2023). "Lithium dispensed for adults aged ≥ 50 years between 2012 and 2021: Analyses of a 10% sample of the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 31 (9): 716–725. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2023.03.012. ISSN 1064-7481. PMID 37080815. S2CID 257824414. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search